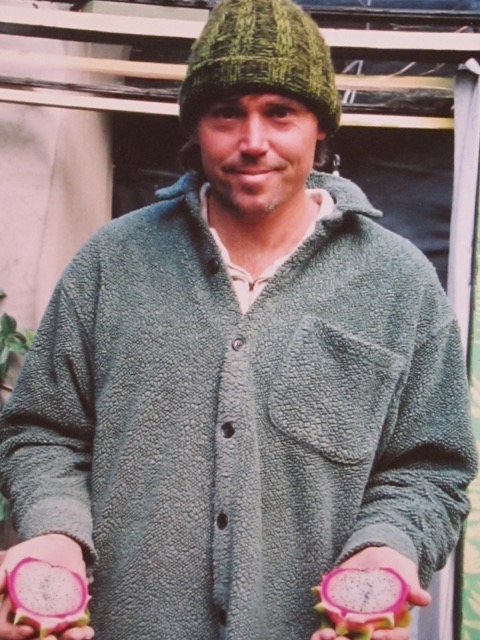

Michael Giorgi was born on July 7, 1968 and began his childhood at his family's ranch at Nojoqui Falls, Gaviota. In all of his wanderings, he has always found solace in nature and growing things. Today he works as a gardener and landscaper and lives on the beautiful land he knew as a boy. Here he shares his insights about the magic of the world, finding balance, and nurturing life.

“I think what I would say is that we are here to realize that life is much more than we assume it is. I think that’s what we’re here to learn: that there is something more than what we think it is. There’s more to it than what we expect it to be. So the only way to miss that boat is to not allow yourself to be open to new perspectives or feelings or experiences.”

TO LIVE IN THE WORLD WITH AN OPEN HEART

CW: Earlier, you were talking about living up in northern California, and your sense of a community there, and what was different about it.

MG: Yeah, it started just after high school, ‘cause I went up to Humboldt to go to College of the Redwoods, and that was really the first time that I realized there was a completely different world happening that I didn’t have to travel across the globe to see. There was so much of a counter-culture presence there, really looking at things differently in terms of ideas and values and the way they lived life in general.

CW: How old were you at this time?

MG: Eighteen.

CW: And you had been living in Santa Ynez Valley up until that time?

MG: Pretty much. Most of my life. We moved up to Shell Beach in my senior year, so I actually graduated from San Luis Obispo and we stayed in my grandparents’ house who had been living up there. That was my mother’s mother and father, who had built a place there back in the 1970s. So we’d go up and visit them. They were looking for a little change and they asked us if we were open to a change, even though it was a really formative period for me…you know, senior year of high school is when most people are ready to just take off…but I was rarin’ to go. I was ready to try something fresh, and we were right on top of the beach there, so who could resist? So we ended up going up there, and I graduated.

That summer I took a road trip with a bunch of friends, ‘cause I’d spent a lot of time with friends down in Isla Vista while I was at Santa Ynez High School. So half of my community was the friends from there, and half of my community was the friends from Isla Vista. So I had this little quantum leap of thinking about different possibilities and what was going on in the world, ‘cause that was a very experimental crowd down there. I got really close with them, and they wanted to take off on this road trip that summer, my senior summer.

I had a ’68 Volkswagen van, so I volunteered the van, and we took off to the Sierras for a rock concert up there…and we just kind of explored all these back roads all the way up to northeastern California and then we stayed with friends up in Arcata that they knew, and went all the way down along the coast, and it was probably about two or three weeks’ worth of road trip, and that’s where I really got excited about what was going on in northern California, other than when I was a little kid and we’d take family vacations. My imagination just went wild as soon as I got into the redwoods up there.

CW: Was that the first time you had seen the redwoods?

MG: Other than when I was a little kid, and my mom said I spoke some famous quote about how I never wanted to leave there.

CW: Can you talk a little about what you felt when you were there?

MG: It was like being in the presence of the supernatural. Or being at Disneyland. Or reading a fairy tale. The lines blur and you feel like you’re being transported to some world where mythic beings might step out. It kind of renews your own sense of wonder and your understanding of what it means to be in the world. I mean, there’s plenty of that when you’re a kid, but you’re sort of losing that innocence over time.

And it was a very profound symbol of what I found in nature in general. But there was something about the redwoods…like you actually encountered some god or something...the presence.

And I think when you’re younger, you don’t have as many filters that get between your interpretation of what is magic…true magic....and what people want you to believe is reality.

To me, it was just kinda like: See? Magic really does exist! I can feel it. Look at it. See it. It's all around. And you could see it in everybody’s eyes, whether they were kids or adults, whatever they were focused on, all of a sudden everything just disappeared and all they could experience was the presence of that forest and those trees.

So that was pretty profound. And I think maybe that was part of why I felt compelled to head back in that direction.

The other part was just to be on this wild, crazy adventure with these older friends who I felt were kind of initiating me. So I decided to go to school up there. And I ended up going to the College of the Redwoods and moving up there with a couple of friends that I grew up with.

CW: That’s perfect. You literally went to the College of the Redwoods.

MG: (laughs) That’s true. And actually, it was a great experience but I found it really challenging. It was a very wet year up there and I found myself trying to deal with all the changes of being away from what was familiar to me in combination with what was so exciting about it too. I met some people there that were really influential to me but I didn’t get involved to the degree where I felt I’d really hooked into something to keep me there.

So I ended up coming back here (Gaviota) and working on our ranch with my uncle for a little while that summer, and moving down to Santa Barbara and going to Santa Barbara City College, general education stuff.

CW: Your father had passed away by this time?

MG: Oh, yeah. He actually passed away when I was in fifth grade.

So I still had a connection to the ranch down there, and we’d be back and forth because of my grandmother and I’d spend time with her, and that summer I kind of reconnected in a deeper way with the land, a working relationship with it.

CW: If you’re not tired of talking about it, I’d like to learn more about your relationship to that ranch, to here, and what it means to you. At that time, was this like a transitional place for you, or did you feel comfortable there?

MG: I felt very comfortable. It’s funny because I spent so much time working the land with my dad when I was younger. He had more of his life based on the land. From the time I was about seven or eight and driving a vehicle around the ranch…whatever he was doing, I was just shadowing him and trying to be a man. But he made it fun. So I always felt I had a connection to a livelihood there. It wasn’t just a place to play or grow up. It was almost like I already had a livelihood, in terms of that work ethic.

CW: Was it your grandfather who first purchased that land? Your great-grandfather?

MG: It was my great-great-grandfather. He came over when he was young, with his brothers, and they first came to San José, then started working down the coast as dairymen. When they got to this area they started to lease-to-own this particular piece that’s now Classic Organic. That was the original homestead. It was the turn of the century. They were dairy men, and they started a dairy and that was probably the main thing, but then they had their orchards and their field crops and their chickens and hogs and vegetables…their vineyards, they were Italians…everything, you name it. They just had this incredible work ethic. Live to work. They took a lot of joy and satisfaction in what they were doing there.

They came from a pretty desperate place in a lot of ways. They were looking for a place to emigrate to, as a lot of people were. I think my great-great-grandfather had even gone to Australia at one time when there was a sort of semi-gold rush period going on down there. He didn’t make it, and he came back and sent his sons to America. They had that pressure on them to try to create an anchor for the rest of the family so they could start coming into the area too, which they did. They started leasing more tracts of land and eventually purchasing it. They bought up into that valley there towards Nojoqui, which is the eastern boundary, and that used to be the house ranch, then up and over to the top of the grade and down towards Las Cruces. So that’s where the 120 acres is now, that used to be my father’s parcel, and there’s two other parcels after that, that roll on down the hill that are owned by my two uncles.

CW: You must know that land like the palm of your hand.

MG: I’m getting pretty good at it. But there’s always new realms. It’s funny. You start by following the roads, and then you kinda get off track a little because you see something off in the wild section somewhere, and you go off there and something else will catch your attention…and you’re back in that childhood phase again. You’re seeing things that no one ever sees.

CW: And you can still summon up that consciousness?

MG: Oh yeah. It’s never left.

CW: In that place in particular?

MG: Everywhere I go. I was telling someone the other day… we were going down to a concert in Santa Barbara and we got into some obscure conversation…they were practicing Buddhists and they were talking about what the ultimate reality was and what inspires your awareness of where you fit into that ultimate reality. That’s of course different for everybody. So I started debating Buddhism versus my own perspective, and I could certainly identify with some elements of Buddhism but I was trying to get them to understand the concept of when you’re kind of a wild child, when you’re so immersed in nature, and that’s really what symbolizes the divine consciousness. I wouldn’t say that I worship nature, but it’s something that I try to emulate and try to become an extension of in myself because of course we are nature, and the more we can be familiar with how that exists in us, hopefully the more in balance we can be.

CW: Buddhism doesn’t seem dissonant with that perspective, does it?

MG: I think what they were talking about that day was really emphasizing the non-attachment. They were getting pretty esoteric about it. As soon as you call something “something”, you’re attached to it. I forget exactly what the stream of conversation was, but I was trying to tell them, here we are in a city, and I’m trying to stay centered and grounded in nature even though I’m in this manmade artifice everywhere we go. As we move through this city, I’m always feeling connected to whatever plants or trees there are. Even if I go into a building, and there’s an indoor plant or something like that, that’s what anchors me. That’s who I am, in this place where it’s very easy to be distracted from who you are. I guess I’m trying to tie this back into what I was saying about how I’ve never lost it. I just feel like wherever I go, there’s something that I’m trying to stay connected to, the same way that I have always stayed connected to it since I was a kid. And it just made sense. It’s just naturally where I was, and it’s what allowed me to be who I was, in the best way I could be myself.

CW: So from childhood, you felt that resonance with the natural world.

MG: Definitely. It’s what invigorates me. It feels like it’s what gives me life in a way. Whether it’s inspiration or deep breathing or trying to make sense of what’s going on in the world…and I think that’s what we’re all looking for. What is this transcendental place we occupy that we can call our deepest self, our best self, our spirit, or our soul…something that is holy or sacred?

CW: It sounds like you do have those moments, still, where the filter is removed and you’re just a part of it, like those childhood moments you had.

MG: Yeah. The way I’ve been thinking about it most recently is I've been spending time back at the yurt that I originally came back to. I had set that up in a little meadow surrounded by large oaks next to a stream. It’s got a balance between good sunlight coming through but also good shade. It’s not too exposed to the wind, not too cold, not too hot. It feels like there’s an equilibrium there that I was just naturally attracted to. And I remember as a kid going there, moving through it, and just stopping, and sort of taking it in. There was an attraction.

But if someone had asked, “Where do you want to be on that land?” I wouldn’t have necessarily named that spot. For some reason it was just this real instinctual moment when I was trying to set back up there after coming down from Santa Cruz. So I had a sixteen-foot yurt and I plopped that down there, gradually sort of expanding off of that as a place to dwell and make the transition. But I’ve been back there a little bit more after we moved over to the little studio where you visited us last, and every time I go back there...I’ll be in these funny little quirky moods, where things feel a little off or I just feel a little overwhelmed...and if I go back over there, as soon as I see that, coming down the road, everything just kinda fades away. It’s like a whole other dimension.

CW: So…what’s your typical day like? What’s your routine?

MG: It varies a lot depending on the season.

CW: Are you doing a lot of work for other people, off your property?

MG: I go through phases. I have a work routine, and that becomes the priority. That’s my livelihood in terms of my financial foundation, which allows me to do other fun things on the land.

CW: What do you call yourself?

MG: I just tell people I’m a landscaper and I do consulting and installation and to some degree maintenance, if it’s the right relationship…Everyone has their qualifications and experiences leading up to what allows them to have a title, and for me it was a number of different experiences. Growing things. When I was in Santa Cruz, I was always fond of gardening. Wherever I was at, I’d create a little garden of some sort and just work off of that.

Before Santa Cruz I spent time up in Sonoma County at a farm and wilderness center, which was a 360-acre nature preserve, but they also did a lot of environmental education and retreats. It was just this center for all these amazing horticulturists that had left their legacy on that land, so I came in and left a little of my own mark but also tended what they’d left, and I got to experience their relationship to the art of gardening and living on the land.

When I got down to Santa Cruz I was renting and living on a ten-acre piece of land where I started a project with the son of the owner who was also living there and also loved horticulture. We rented an old orchard that his father put in but was neglected. It was a lot of stone fruit, but it was a very sandy soil, and the thing about sandy soils is you need to add more input to them for fertility on a regular basis. So we thought, “Let’s start a little nursery where we can grow and sell plants.”

I was really fascinated by salvias. There are just so many different varieties, and there were a lot of collectors up there where we could get information about ‘em. They’re what I call kind of a multi-use plant. You can use them for ornamental value, or making bouquets, or their beneficial insect qualities.

CW: And they’re drought-tolerant…right?

MG: A lot of them are drought-tolerant. There’s just all kinds of amazing characteristics that they have.

CW: Do you have a favorite?

MG: A lot of the natives that I grew up with here, as I was hiking in the backcountry, I became really fond of them just because of my memories associated with the places where they grew and my experiences at the time. And they’re really appropriate for some of the extremes we have down here.

There’s one particular one–every year I tell myself I need to propagate like five hundred of these and just put ‘em in everywhere, because they’re essentially native of the island out here: Salvia brandegeei. Every time they start to bloom, during a three-month period: last month, this month, and next month, you can have every single kind of insect that is native to the site, on that plant. Most insects are more partial to certain kinds of plants, but it seems like everything wants this flower. So you have this huge party raging. And what’s good is you can plant it as a drought-tolerant hedge around anything, to bring in predatory insects to help manage what you don’t want in your garden, or increase pollination of other fruiting plants. So it helps establish a balance.

Anyway, we started a rare plant nursery up there and we grew a lot of those. We were down the road from Bonney Doon Winery at the time and a lot of weekend tourists would come up there for their wine-tasting, so we put up a little sign that said “Plant Tours”… for people who wanted to walk off the buzz from their wine tours a little bit and check out a beautiful local site, so people would show up in the garden where we’d planted all these plants and they’d get inspired, and we said we had ‘em for sale, and they’d buy some and take ‘em home. So it helped to fund the project. Not only did we earn a little money to make a living, but we also renovated the orchard. We put all the pots that we grew the plants in underneath the trees so that all the watering and fertility that was in the pots kind of leeched back into the ground, and the canopies of the trees provided a partial shade so we didn’t have to water as much, and everything looked fuller and more lush.

We were also growing a lot of food for the people that lived with us. We had about eight different household members in an old 1880s restored farmhouse on a beautiful piece of land. There was a circle of redwoods right behind the house, and a naturally occurring stream. It wasn’t a commune…it was only ten minutes from town and everybody had their own little thing going on. But people still had an appreciation for getting together. We loved it. It was so much fun. And your whole network of community grew through those individuals. It was a way of reaching out and creating a place where community gathered and grew.

We grew edible flowers. That was another part of our venture. Inevitably, what would happen is people would come in from the local mountains and Bonney Doon, the whole area to the north of UCSC as you start to climb into the mountains there, that whole coastal range as you go north to San Francisco, people would come in and say you have such a beautiful garden, do you do any installation work, or do you do any consulting? I’d say sure. So it just took off from there. Coming back here, I’ve been really fortunate to meet some wonderful people who have been really supportive of that.

CW: So what prompted you to come back here?

MG: I had been away for almost fifteen years at that point. All of a sudden there were a lot of huge transitions in my life that kind of caused everything to go sideways. I fought it for a while because I’d been in Santa Cruz for almost ten years by then and was growing this business and had this whole community up there, but I was also feeling that…well, one of the things was I’d be growing these gardens, these beautiful places, and the landlords would say, okay, you gotta go. That happened so many times. I tried to pick and choose situations where I’d have some kind of stability, but inevitably things would happen in people’s lives. So I just said, "This is ridiculous. I’ve got this beautiful 120 acres back home." And I felt like there were responsibilities I had there that I really hadn’t picked up.

CW: It seems like a natural progression, when you think about it. Maybe you just had to go somewhere else for a while.

MG: Oh, I definitely had to go somewhere else for a while.

And back to an earlier conversation, about Lori and me…that’s what brings up those feelings that cause us to wonder have we completed a phase here? Have we done what we needed to do here? Because we both have these longings for other places that are different in some ways. And we’re both really adventurous. We both still love going out and meeting new people and being immersed in new ways that other communities offer. Each one is distinct. Maybe it’s all just California, but there are some really different populations and groups of people even if it’s California.

CW: So the idea of just staying here now feels…well, maybe you will and maybe you won’t?

MG: I think at this point we’re pretty rooted. It’s hard. We always go back to checking in with ourselves and we don’t want to take any of this for granted. I think everybody’s always trying to switch it up a little to make life interesting, and when you’re in a place you get involved in these routines and they’re wonderful and inspiring and give you a sense of security and a sense of place and meaning and community, and they really drive you in certain ways, but they reach their end point and you have to re-examine what those relationships are to you, and how to change them up a little or find other relationships as well.

CW: I don’t know if that ever stops. I think you just become old and tired and the idea of moving feels like too much trouble.

MG: (laughs)

CW: Or the things you need change.

MG: I think routines can make you feel tired too if you’re immersed in them longer than you should be.

CW: When I look at your situation, and Lori’s as well, it’s so unusual for people to have such a connection to the land over generations. Lori said once that she was gardening in the same dirt as her grandmother, or her great-grandmother. It’s so unusual. It’s probably the way things used to be, but so unusual now. And in a way there’s something so beautiful and compelling about it. It feels like it would be hard to walk away. And it’s not like this is an ugly place.

MG: Absolutely not.

CW: You almost wonder, what could be better?

MG: That’s what I keep going back to. If we need a little escape, let’s just jump in the car and drive a couple of hours up to Big Sur, and you have a whole different world there.

CW: To me, I sometimes think what I’d miss the most if I moved are my friends. The network of people…it’s taken a while, but I feel that we have an amazing little community of friends. That would be hard to leave.

MG: It’s true. And we barely have enough time for those people. I really cherish those moments too. I think maybe part of it is trying to work to create the moments that are really unique and special with those people, which is kind of an art.

CW: How do you do that? Life just happens so damned fast. When you finally figure out what you should have been doing, that part is over. How do you claim your life? How do you grab it and make it yours? What are you doing?

MG: (laughs) Back to being in nature again. It’s about trying to remember what helps me to slow down so I can be human and not a machine.

CW: In your case, isn’t nature part of your work? How do you separate the experience?

MG: I always have the excuse to tell my clients: you can’t make the garden grow any faster. If you want it to be the way you want it to be. I always have the excuse to slow down.

But it’s true, if you want the work, a lot of people want instant gratification. They’re used to that in their world. And a lot of people have the means to have that all the time. So you’ve got to find that balance of presenting them with something that gives them that big charge that they’re after in terms of the product, but at the same time…

For me, I like the challenge. I like to push my envelope a little bit in terms of what I choose to do: the pace of it, or the technicalities of it, or the formalities of it, whatever. If I can do that and bring it to a conclusion that’s satisfying to the client and myself without losing my own integrity in the process, then I feel that I had a good reason to go back and do what I need to do to nourish myself.

But there are a lot of elements in being a gardener for people where you do get to slow down and be with nature in the process.

CW: So, Lori and I are always asking people: how do you navigate through decision points or difficult times? What would be your source of strength, or your compass?

MG: Difficult times. I think that goes back to what you’d call a spiritual path or a spiritual perspective. For me, one thing that nature has taught me is that there’s no good or bad. Those Judeo-Christian model things, judging things as good or bad…I try to look at things more non-dualistically. Everything has something to offer you when it comes to being complete. You get out of balance. Life is out of balance.

CW: Remember that movie, Koyaanisqatsi?

MG: Koyaansiqatsi. Isn’t that what the word means? Life out of balance. And so everybody has their way of restoring balance. What are our needs? Some are basic to everyone and some are individual. I think the best way to get through those times is to check in with yourself and say, “Hey, there’s an opportunity here.” I may not be feeling what I want to be feeling now. I may be feeling conflicted, or dark, or low energy, or hopeless, even. But if you can just kind of check yourself you see there’s an opportunity to find balance in some way. Whether you’re out of balance because of poor choices, or you’ve just come to the end of a cycle where something needs to change, it’s a transformative moment.

Everyone, through life, gains a little bag of tricks about how to nourish themselves in ways that give them a little stability. Life can get really dark. Sometimes just seems like anything you try to grab onto, you can’t find a firm foothold. But maybe at those times you’re supposed to be free falling; maybe you’re supposed to feel helpless. Maybe you shouldn’t be in control at that point so that something can come to you that you’ve been resisting, because if you’re in control you obviously have these ways of keeping things at bay.

I think life sets us up for success but it has a different set of elements and boundaries that it does that through. They’re not a human realm. They’re forces of nature. You have these horrible events in nature that seem really cataclysmic…a tsunami, a drought…but it’s doing that to try to create a balance somehow. We can’t always see why, but eventually if we let go of our own expectations and what we personally want, maybe other things can come to us about what is important. It may not be what we would choose. And maybe we can find a little meaning then in the suffering that allows us to let go too, something that opens another door.

And I think, like that old saying that gets over-used: time heals all. If there’s a loss we’ve been going through, a loss of sense of self, or of something that’s familiar to us, I think we grow into something new and fresh. And we can’t go back. We can never go back. But in some ways, it’s really good that we can’t. Because if we keep going down that path, we get to these really wonderful places that are unique onto themselves that start a whole new chapter that’s just as gratifying in other ways.

It’s a perspective. I guess for me in terms of practical steps, one of the things that nature has also taught me is about groundwork. You’ve got to have a healthy soil before you can grow a healthy plant. For me the groundwork is my body. Making sure I’m well nourished. Making sure I get enough sleep. Exercise. All the stuff everyone tells you.

CW: Have you had an important teacher or mentor in your life?

MG: I think everybody I meet. It’s really true. There are some people that really have this luminosity about them. Wow, I wish I could be more like them. But then there are people that seem like they’re completely nuts, or ignorant, or whatever, and they’ll say something, and if you can get out of your judgment, all of a sudden, it will have some relevance to whatever you’re going through. I don’t know if you’ve had that experience, where you’re walking down the street, and some homeless person says something, just babbling, and they’ll just say something that seems like it’s directed at you.

CW: I don’t know that I’ve had that experience, but I notice I’m not so quick to dismiss someone as being irrelevant. I’ve started to notice that everyone has something…some gift, some wisdom. Well, sometimes it’s hard, but I’ve been trying to be more accepting and patient.

MG: You do have kind of a child-like sense of wonder about what is unique in people and their experiences, a very authentic sense of fascination.

CW: As do you. But I think wonder and fascination come with being here. The fact that I live here is intrinsically amazing to me, and so implausible, I don't think I'll ever get used to it. Talk about nature. The natural world is so palpable here. We can’t ignore it.

MG: It gets right back in your face. It wants you to participate on some level.

CW: I do have this feeling that there’s something really important about this. That nature is the bottom line. In some ways, as individuals, we’re insignificant, but we’re also part of this vast, interconnected picture. We understand so little of it, but even the little that we understand is so mind-boggling. And it seems that nature is a way of connecting to it more readily, a way of accessing the wonder.

MG: Yeah. I guess there’s different ways of people approach nature. A lot of it is just entertainment. You see that here quite a bit. A lot of people come up to recreate. And that word, that was a whole field of study I was looking at when I was trying to figure out things in college. Re-creating yourself through nature. Sounds good.

CW: When you were working as a gate guard at Hollister Ranch, that was something I always appreciated about you. You understood your role as the facilitator for people coming up to recreate, transitioning from that world to this one.

MG: My whole field of study was about that. I went to a liberal arts college in Prescott, and you had the option of creating a title for your own studies. So one of my competencies at the time was what I called “Human Nature Integration.” (laughs) It strove to combine the human development field with environmental studies or outdoor recreation experiences. Another term that was being played around with at the time was wilderness psychology. The school emphasized a lot of fieldwork. Students would go out into the field; as soon as you got there, you would go out on this three-and-a-half-week wilderness orientation…in the wilderness, the Southwest desert. On the third week of that you had a three-day solo, where you had the option of fasting. And I did. It was the first time I ever did that.

And it was also the culmination of a huge monsoon storm that came through, and I had forgotten the strings to tie down my tarp at the time. They would just give you the minimum amount of things to take care of yourself while you were there; then they’d come and check on you every morning. But there were these quintessential moments where it was very powerful and transformative. Like, this is why I’m here.

CW: Did you ever feel afraid?

MG: Oh yeah. All the time. (laughs) First of all, I was leaving this place that was my home, that had all these familiar reference points, whether it was being close to nature or being around my community or whatever. But I was also at a point where I was just willing to cast myself to the wind. I wanted something completely different and I was willing to make whatever kind of sacrifice would do it. I was just feeling so stuck here where I was at. It was after I’d come back from being up north, Humboldt County. And the precursor to that was I’d been on an Outward Bound course that my mom had given me as a birthday gift. It was out at Joshua Tree. We hiked under the full moon that whole week.

As I tried to figure things out and find out what was inspiring to me that I could move towards as work, I was looking at possibilities of leading groups out in the wilderness for human development purposes, like Outward Bound. But then the woman I was with at the time did that, and she was doing a lot of fieldwork, and she’d be gone for months at a time, and it was like one of these long distance relationships. It made me feel like I’d never have a home. I’d be kind of nomadic.

So that’s why I put this twist on it. I’d try to come back and live in a place where the garden became the symbol of the natural world and I see what it could teach me in the place where I resided. So there’s kind of an underlying element here in terms of the landscaping and what it could teach me. And the whole premise of Human Nature Integration was to look at why we’re out of balance as a human condition. You can address that through any topic or any conversation, and it’s very complex. It’s a field that’s emerged…it’s called Eco-Psychology now.

But the garden is a great way to look at symbols of how we’re out of balance. It’s a place where people can check in and get inspired by something that is the natural world but also has themes around, for instance, where does your food come from? How important is that to you? What are all the other issues around food importation, or organic versus nonorganic? And it goes on and on.

So you can look at it in a practical way through those types of themes, or you can look at it as in, how is this a sanctuary space for you? What happens to your whole psyche when you go into a place of nature that provides you peace and clarity?

That’s an extension of what my experience of going out into the wilderness or nature was: a place where I could find meaning.

CW: I’m just curious. When you say you have had transformative experiences, how does that manifest itself? Where would it have been?

MG: (laughs) It happened daily. I don’t know how I could choose just one of those instances. It was that time of life in my twenties, early twenties, I was just going through this incredible transcendental moment when it came to every aspect of who I was, from getting involved in my first long-term relationship with a lady, and everything that came out of that…I got really schooled by her. She was a hardcore feminist who led groups up to the top of volcanoes. (laughs) I learned a lot there that was very transformative.

And I did some service work at the Yavapai Apache reservation. I had a childhood development course I was taking and I had to do a project, so I went over to work with some kids on the reservation and I met a man there and he was friends with my partner at the time, and they were doing a lot of Native American sweat lodge stuff, so he invited me to be a part of that, but that was kind of a mixed sweat with all different people, but he also did sweats for Native American veterans, and that was the first thing I got invited to, as I worked with his children and got to know him, he said, hey, wanna help me chop some wood and build a fire for this ceremony? And I didn’t know anything about it, I was like sure, it sounds exciting, different.

So next thing I knew I was tending fire for a very traditional sweat lodge ceremony for ten Native American veterans that were going through some really intense moments in life. And out there, that’s full cultural immersion. They’re all speaking their own language, and they’re kinda giving you the stink eye ‘cause you’re the white guy tending the fire. As much as I love nature and stuff, I never had this romantic notion of wanting to be an Indian, so it was kinda just this innocent place I found myself that kinda grew on me, being part of those ceremonies.

And just…the Southwest is such a different environment, elementally in a lot of ways. There’s a lot of subtlety to it. Out here in California where I grew up there’s so much diversity of life in your face in terms of the natural world. It’s so dynamic, in just in-your-face ways. When you go out to the desert, it’s seems so barren and quiet, like there’s not a lot going on, but as you spend time with it, it’s just on a subtler level. There’s all these profound things going on. So maybe in a way it taught me to pay more attention to things in terms of my environment. That’s why it’s always been this place where people go for spiritual experience.

CW: What I see in you, though, that’s so admirable is that you have that quality of being open, of being willing to experience it. That’s really a gift.

MG: It’s such a birthright in a way. Everybody comes into this world with that and for some reason or another it starts to shut down.

CW: Well, some people hide. Or they don’t recognize the invitations. It takes a certain amount of courage, or spirit. It’s cool that you are so open to these kinds of things.

MG: You know, just thinking about it in the moment it occurred to me that maybe part of that is growing up on a ranch. Because you’re not as pampered on a ranch. You’re just like another animal. You’re given a little more freedom to experience all the different sides of life, whether it’s falling down and getting hurt, or getting bit by something, whatever it is, it’s just part of the experience. So maybe I just realized that was they way it is in life. And it’s not so much to shy away from, it actually leads to these really wonderful sensations and ways of seeing the world that maybe other people don’t embrace because they’re holding back, or they’re held back, or they hold themselves back as a conditioned response.

CW: That’s an interesting angle. But I also think you just live on a different level. You’re hearing things that most of us are missing, seeing things that most of us don’t notice. Do you still go out in the moonlight and pollinate?

MG: (laughs) I figured out a way to do that first thing in the morning now, before I go to work.

CW: Oh. It doesn’t sound as romantic now. What’s your favorite time of day?

MG: I’m more of a morning person. I was born at 4:20 in the morning and sometimes I wonder if that’s why, ‘cause a lot of times I wake up at that time, no matter when I went to sleep. There’s just this moment of clarity. Freshness. Kind of a reminder that life goes on. It starts fresh again. My alarm clock is bird song, and sometimes the moon at night, sinking on the western horizon. There’s all these little subtle things in nature that are my clock.

CW: And your favorite place in the world?

MG: I was just thinking about that the other day too…I’ve been thinking about death in a lot of ways…where people have their ashes scattered, you know. If it was up to them to decide or if it was up to someone else to decide, “Oh, this is a good spot because they liked to come here.” And I wondered where that would be for me, or where somebody else would decide it was. I don’t think I came to a conclusion.

The one place I was thinking a lot about because I’ve been going there a lot lately has been Big Sur. There’s a creek called Salmon Creek that we’ve been hiking up and it’s sort of the gateway, it’s where I see…here, you have this really profound transition, Point Conception where north meets south…but to me it’s more like southern-central than northern California, to me, it’s southern meets central, somewhere between Pt. Conception and Big Sur, and Big Sur seems like where you really get into central California meeting northern California, so there’s a couple of places when I’m going north there’s a couple of places where I feel like I’m finally letting go of everything that holds me down in southern California, that kind of feels heavy to me. And Big Sur is one of them.

And when I go across the Golden Gate Bridge and I go through the tunnel with the rainbow…(laughs) I know I’m in northern California. But Big Sur is a pretty profound place to me ‘cause it’s really a great example of untouched wilderness, and it’s a place that has a really transcendental element to me in terms of just how pure it is, and how much you can go there and everything else that feels heavy to you just dissipates. Everything that you were worrying about, you realize just isn’t that big of a deal, ‘cause look at what’s around you. But also, the inspiration of it, how beautiful it is, all of its seasons. You see that in everybody’s experience of it.

CW: What inspires your creativity?

MG: Probably looking at the world in a fresh way, whatever brings that out, which is why I’m such a nature addict, because no matter how many times you go out, you’re bound to find something new if you’re looking the right way.

CW: And you’re creative about the way you approach your agriculture.

MG: Yes. So that inspires the way I create in my garden, and the kind of projects I do. I think even with cooking. I’m so fond of food, ‘cause it’s a direct extension of that place. All of a sudden you get on a roll of seeing that interconnection again. Everything is an extension of that if you look at it in the context of what I’ve been describing. Even human experiences, storytelling. In the same way you might watch the life stages of a seedling developing into a plant that you harvest and make into a great meal, you can almost hear in someone’s journey’s the emergence of their sense of self and see them growing into what it is that other people celebrate in them, and that offers something nourishing in the world. There’s a lot of parallels that way.

I get into a lot of ruts. Recently I’ve been feeling uninspired in some ways. So I always think what do I need to do a little different? How do I switch up the routine a little bit? And it’s tricky, you know. I try to keep it healthy, whatever it takes.

CW: Do you find that a good hike refuels you?

MG: Definitely. And I’ve been doing a lot of weekend trips up to Big Sur for that reason. And it’s guaranteed. Every time.

Or just on the land. That’s really the most important thing. You know, making a good meal with somebody. Finding people that like to celebrate the same things that I do helps to inspire creativity. Things that you can be collaborative with, that help you to feel you’re integrated into a deeper sense of community with the people you occupy that place with, as well as feeling like you’re integrating into the natural world itself. Just tying all those threads together in some ways, feeling like you’re really finding meaning and passion in life in ways that all your experiences culminate to help you focus on doing. Just making all the right choices so that energy can really flow.

Sometimes it’s just a matter of…have I gone out and really breathed deeply that day? (laughs) Like, how come I don’t feel the flow? Oh. I’ve been driving in my car all week. Or I haven’t gotten enough sleep.

CW: What wisdom or advice would you like to give, say to a younger person?

MG: I guess maybe just try to learn how to be true to yourself, and how to live in the world with an open heart. Don’t be held back from allowing yourself to experience it all and finding meaning in it all. There’s so many imposed parameters for what we should or shouldn’t do. Either we’re the ones telling ourselves, or somebody else is telling us, and I really think people need to kinda take more of a walk on the wild side in some ways. I don’t mean just party hearty…I mean, put yourself out there, on the edge and look at what you’re afraid of and try to move through that, and see what happens. Don’t be afraid to fail. Look for revelation and rapture. There are all these profound feelings you can have…and indulge in everything you can. Be ethical about it. Try not to hurt anyone in the process. (laughs)

But at the same time, why…I mean, civilization is a good thing, I’m not saying we shouldn’t be civilized beings, but there’s just so much more that we can experience through our senses and intuition and minds. We’ve got this brain up here and we’re just scratching the surface of it when it comes to how much of its potential we get to experience. It’s not just about mathematical equations, figuring out how to speak properly…I just think there are really magical things that can come out of all the different parts of being human if they can inform each other. I think we get too preoccupied with being one thing or the other and thinking that’s all there is to life.

CW: There’s value in all those different parts of being human if they can inform each other. I like that.

MG: Yeah. I think it’s all geared to trying to understand what human potential is. Everywhere I look, I just think there’s so much more to human potential.

CW: I keep feeling like there’s something we’re supposed to learn. Here we are in this really weird thing called life. It’s so odd, and it happens so fast. So we’re either supposed to learn something or evolve into something or…I mean, I worry that I’m gonna miss the point, whatever it was.

MG: No, you’re not missing the point. I think what I would say is that we are here to realize that life is much more than we assume it is. I think that’s what we’re here to learn: that there is something more than what we think it is. There’s more to it than what we expect it to be. So the only way to miss that boat is to not allow yourself to be open to new perspectives or feelings or experiences. I guess just do away with the assumptions.

CW: The last question I like to ask people, which doesn’t mean that the conversation has to stop if you think of something else you’d like to add, is…well, it’s easy to get depressed and overwhelmed…we’re constantly being inundated with a lot of sad news and worrisome things. So what I want to know is what gives you hope?

MG: That the sun rises every morning. (laughs) And that it’s a new day. A lot of crap may have happened the day before, but there’s just something about the moment when a day dawns anew. There’s something inside of me that just has faith. I know there’s potential for good things to happen.

And even if bad things have happened, that there’s meaning in that that’s going to allow something better to happen. Maybe seeing people’s responses in hard times that are just beautiful, passionate, positive, perfect, impeccable ways of dealing with that moment. Where you just think, I would have just fallen apart; I could have never handled that. And you see someone just coming to that moment and acting in such a graceful way.

And just beauty.

Meeting strangers you think you’ve known all your life, that you feel really connected to, and you almost feel that you’ve started life anew because of them.

CW: How would you like to be remembered?

MG: (laughs) I think about that too. Every time someone dies, you go to a memorial, and that makes you think about how it’s gonna be when it’s your turn. Sometimes I feel like I don’t know if I even want to be remembered. ‘cause the more people are sad about remembering me, the more they’re pulling my spirit back from moving on, in a way. Because I feel like there’s that bond, in a way. I’d rather just have people wish me well in my next phase of the journey and leave it at that. I think there’s that whole ancestral connection; it’s really an important part of a lot of spiritual traditions in the world, and people build altars to their ancestors and do a lot of spiritual things around it, and of course we all have our own dreams and memories and connections with those that have passed and are important to us. I feel that we all live on in those connections with those still living. I guess…how do I want to be remembered?...I guess I want to be remembered as having somehow offered someone a quality of life that lives on in them, something that reminds them of the potential they can create in themselves. I think that’s how it is for me. This person isn’t here to do this anymore, and I’m really inspired to do it. I guess I’m not being very specific.

CW: No, there’s no prescribed way of answering that question...

MG: Maybe I’d like people to think about how they can nurture life. I can be remembered as some kind of connector to the natural world. More specifically, I hope I’d be remembered in a way that inspires people to try to grow more gardens.

CW: You will! You are someone who grows things. Instead of hurting things, you grow things. Instead of discouraging people, you inspire them.