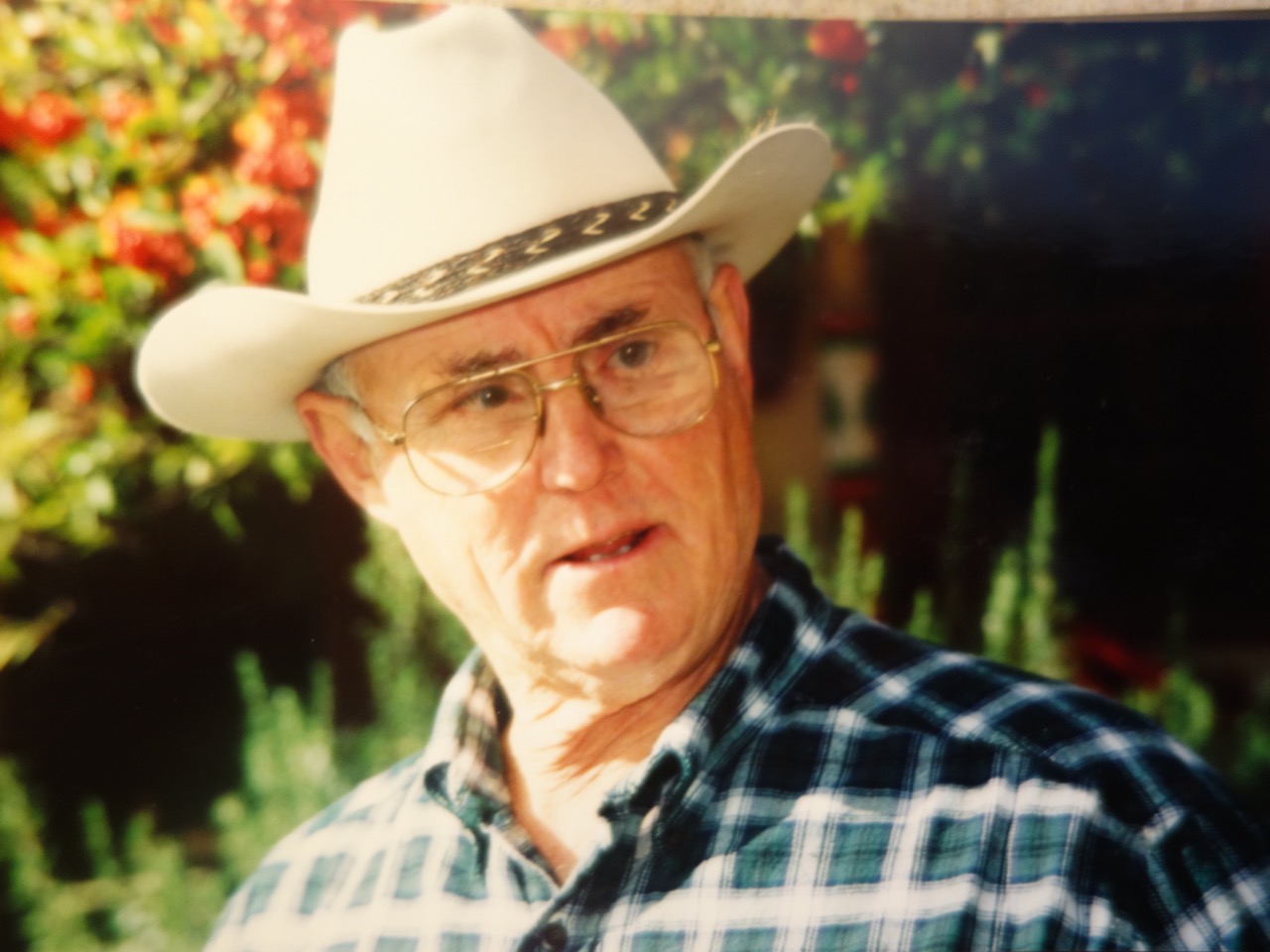

I met Ron Hooker on September 19, 2025 in the reference room of the Lompoc Valley Historical Society, as arranged by Karen Paaske. Also present were Ron’s daughter Valerie, and a local friend and volunteer, Beth Dunn. Ron, who is remarkably robust at 94 years of age, was born in 1931, but not exactly in Lompoc. As he explains, there was no hospital in Lompoc at the time, and when he was “about halfway born” problems arose, and mother and baby were rushed to the hospital in Santa Maria. He is nevertheless very much a Lompoc native, having lived here all his life.

Ron’s father left when Ron was still a baby, and he was raised by his mother, uncle, and a network of loving and diligent relatives. He met his future wife, Dolores Linneman, when they were children. “She used to live across the street from me,” he recalled. “She said that when I was about seven years old, I threw rocks at her.” They met again in high school, Class of 1949. They were married for 66 years.

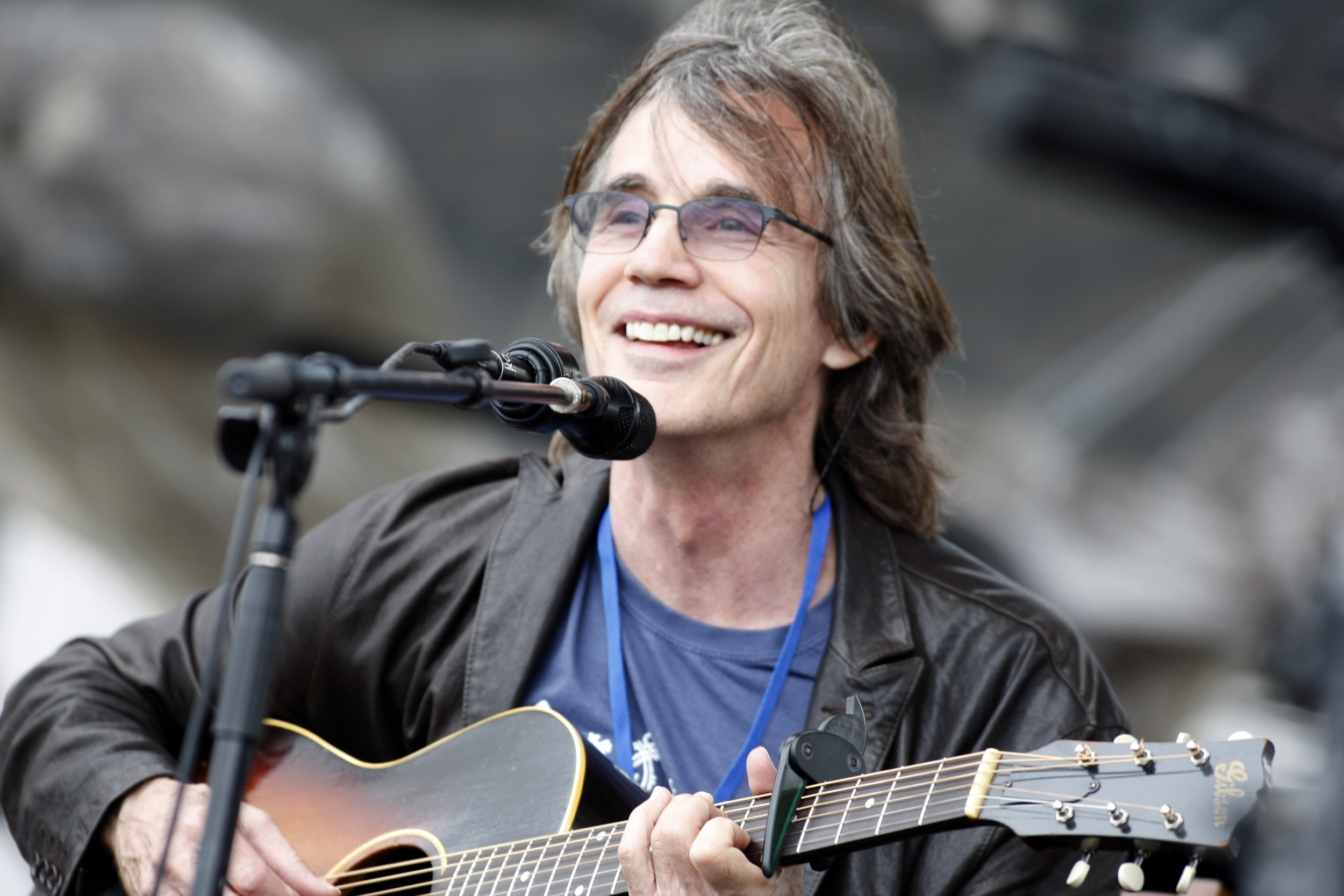

Ron Hooker in high school

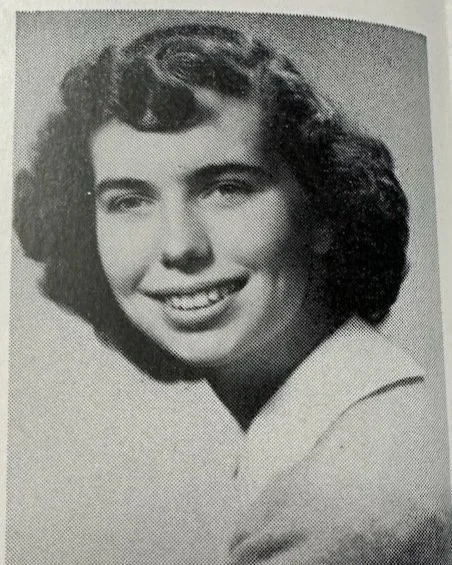

Dolores Linneman, Ron’s future wife, in her high school senior portrait

My preliminary research about Ron mentioned a business called Valley Rock, which he started in 1983 and sold when he retired at the age of 61. But Ron has a long history of hard work, and held many different jobs throughout his life. At the age of 16, he worked at a service station that included a tire repair and body shop; he was entrusted with the keys and the combination to the safe, in charge and on duty even on Sundays. Despite one minor mishap in which the door of a brand new Pontiac was nearly torn off, Ron grew in skill and confidence, and eventually he opened up his own service station, Valley A, with a $200 loan.

He pauses to remember a young man he hired, who left to join the Air Force and was killed while parachuting from a plane during a training exercise. “I’m sad to this day,” he said. “He was such a wonderful kid.”

The next stop in Ron’s career was a job with Williams Brothers Markets. He was a checker and stocker, but he got to talk to the guy from the Lompoc Record about the store ads and eventually was put in charge of advertising there. “I took care of Safeway, and Linda’s Furniture Store, and J.C. Penney,” he says, “and I joined the Chamber of Commerce and got to know everybody.”

Knowing everybody led to a gig with Burt Romano running a liquor store, and seventeen years at Janssen’s Liquor Store.

And all of this does not include Ron’s time as a roustabout with Union Oil, where he started out climbing derricks in the oil fields. Ron met every test.

With stunning versatility and entrepreneurial spirit, he and his wife ventured into the realm of “hamburger joints”, opening up Jolly Cone, Taco Tiera, and Rondo’s, as well as two markets, during the 1960s and 1970s. They worked hard, raising a family, and always an integral part of the community, cherishing the small-town feeling that still prevailed.

Ron remembered a Lompoc where you waved hello at passing cars, stopped by to check the progress of a new house being built, and basically knew everyone.

“I was related to half of them,” he adds with a chuckle.

“Just the other day I was thinking about when I went to school at South F, and I had to walk all the way across town. And I was thinking about the people I saw as we walked. The first place we passed was Mrs. Talbert’s place, and she quite frequently would give us cookies in the evening when we were going home. And then we would go past my cousin's place, George Howerton, and he worked on the garbage truck, and he always had something he picked out of the garbage for us. Usually it was knives, and almost all of them had a broken blade, which is why it was in the garbage. And then I walked by the fire department and Chief Everett would always talk to us.”

“Sometimes there was time to buy a watermelon. They were very tasty, and they had a scale and you pick out a watermelon and you had to weigh it and you multiplied that by two cents a pound and you put it in a cup and that was it. Oh, we had the best of watermelons, two cents a pound.”

“And sometimes, in the dark, we’d go to Schuyler’s Cherry Orchard.”

(There followed a bit of cherry-picking reminiscences. Apparently there was another orchard on Seventh street, and the whole lot was cherries, and Jimmy’s uncle would hear the kids out there stealing cherries and shoot his shotgun up in the air. Good times. Sweet cherries.)

“It's all houses now,” muses Ron. “Most of that area when I was kid was beans. I mean, everybody had beans, and there was a house and the family that lived there made a living on that acreage, but there's no houses anymore, no families. It's all owned by corporations.”

Pivoting from Lompoc nostalgia, I asked Ron what his source of strength is. He answered without hesitation: family. (I was even treated to a picture of his great-grandson, Grayson, who recently participated in the Junior Olympics as a swimmer.)

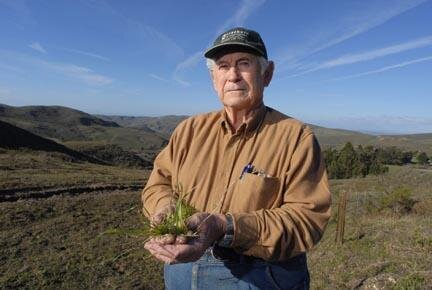

I also wondered if there was a special place where Ron finds solace, in his memory or current life. “I love the hills all around here,” he replies. “I go to Lookout Mountain, which you can't get up anymore, but you can see the whole valley from there. That's what I love. The hills, the outdoors.”

Any advice for young people? Work hard and don’t give up. That’s certainly what life taught Ron.

Ron Hooker is twenty years older than me, and he seems to possess more energy and enthusiasm than I do. And although he is not inclined to philosophize and give advice, I begin to see what keeps him going. Family, yes, and ongoing connection to friends and community, but he is also just curious, industrious, and engaged. He cooks, he gardens, he observes and learns and tends to things.

Roses, for example. He learned to care about roses seventy years ago from his uncle and his grandfather. His grandfather lived on Mission Street in Santa Barbara, and he would always be working in the yard on Sundays, and he showed Ron how to make compost tea for the roses. Apparently, that’s the secret: compost tea twice a year.

“Also, I’ve had seventy years to weed out the bad ones,” he adds. “If I plant a rose and it doesn’t do well, I give it two years, pull it out, and find one that thrives.”

Roses require a bit of trial and error, he explains, and even subtle differences in microclimates are significant. Sometimes a rose does poorly in the backyard and just fine if you move it to the front. Ron is still learning and enjoying the challenges and the beauty. The best-smelling rose, in his opinion, is the Pope John Paul, but his all-around favorite is a yellow rose called Julia Child.

The man is a cook, too, originally inspired by his mother’s chocolate meringue pie. Today he has an oven that holds three casseroles, and that says a lot. He described a chicken mushroom creation that sounds divine, and sent me the recipe later. I hope to serve it to dinner guests soon.

Karen asks Ron why he is in the Lompoc Hall of Fame, a tribute he is too modest even to mention. He said he isn’t sure, maybe because he was a track and field star, and participated in clubs. He doesn’t take himself too seriously, and that’s part of his charm. He fondly recalled his high school coach, Mr. Such, who encouraged him to try decathlon events and compete in track meets and excel in ways he had not known he could. (That’s the thing about teachers…they do change lives, and they are remembered.)

When you look back on your life at the age of 94, I ask Ron, did it all happen fast?

“Yes,” he replies, “And it picks up speed.”

I guess there’s a message in that. Something about paying attention, slowing down, savoring, and sharing. I do these interviews because I appreciate people like Ron Hooker and the folks at the Lompoc Valley Historical Society who honor the stories, who have a sense of community and friendship, who understand that we are bearing witness.

Following our interview, we walk over to the museum in the 1875 Fabing-McKay-Spanne house for a tour of the rooms decked out for autumn. We come upon a display of the front page of the Lompoc Record from January 17, 1949. The headline reads: VALLEY GETS ITS FIRST SNOW.

And Ron stands there remembering, as though it were yesterday. He confesses that he had already ditched school that day and was playing pool at the Bendashers’ place, but as the big flakes fell, everyone left school, and there was an air of festivity and excitement.

“All the hills were white with snow. We went up Miguelito Canyon, there was a little more snow up there, but you couldn’t get over the grade at all with a car. All the hills were covered for two days, which was unusual…you could build a snowman and it would be there the next day. We sledded down the hills on pieces of cardboard. It was amazing. January 17, 1949.”

We’re time traveling. It touches my heart.

I have been invited to the Lompoc Old-Timers monthly luncheon. I feel honored.