A Visit With Doc Macomber at Dunn School

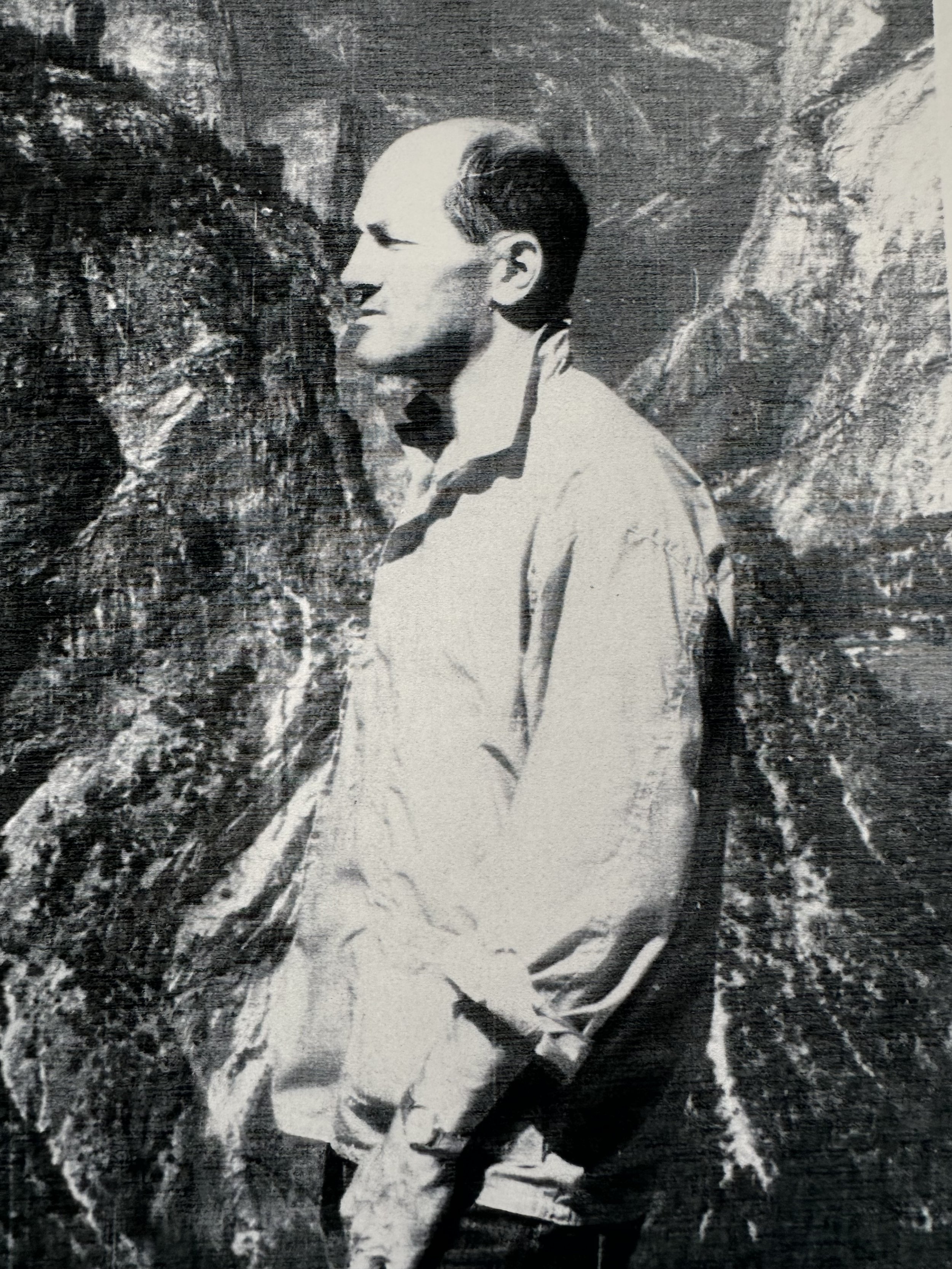

Bruce Edkins Macomber (1930-2021) affectionately known as Doc, was a living legend at Dunn School. Born in Illinois, Doc grew up during World War II and discovered a love of learning early on. He became a geologist and worked for several years with the Shell Oil Company. Fortunately for all of us, Doc found his true calling and became a teacher in the early 1970s. Doc's life and the history of Dunn School had been intertwined for three decades when a few of our middle school students interviewed him as part of our oral history elective in the early 2000s. Doc arrived for this interview carrying scrapbooks of photos and clippings to share with the kids. He was gracious and kind, as always. I heard only recently of his passing, and I decided it was important to honor him by posting his reminiscences here on The Living Stories Collective website.

In his own words:

I was born in Evanston, Illinois and lived most of my life until college in a town called Winnetka.

I went to a public high school, and then I went to Princeton, and after that, I got a master's degree at Northwestern, and I got my last degree at Rutgers -- always in the subject of geology. After getting my doctorate, I spent eleven years with the Shell Oil Company as a production geologist.I went out in old oil fields to find new places to put wells and get more oil out of the ground. After eleven years of that, I decided I wanted to try teaching, and so I came to Southern California.

My first year of teaching, I taught at the Howard School in Montecito, and after one year there, I heard that Bill Webb was looking for a math tutor at Dunn to go with his learning skills program, which was the first learning skills program in Southern California. Mrs. Roome started the reading and writing side of the program and they realized they needed someone to teach math, too, so I became a math tutor. Next year, the science teacher quit, so I got that job teaching chemistry and physics. I did that until I retired, which was about 1996.

I started at Dunn in the school year of 1974-75. The school was very different then than it is now, and the difference is due to the efforts of an enormous number of people. It's very impressive to realize what human effort it takes to change a small school or a small business. I think one of the nicest things about my teaching career has been watching Dunn grow from this little converted farm with dirt roads to what it is today. There was one soccer field where the old grandstand used to be - I remember there was one grounds keeper who worked all the time trying to fill in gopher holes. Then several headmasters went by, and when Ed Simmons became headmaster, he began to raise money, and the first thing he did was build a new science lab, and that was a real surprise for me. Up until then, I taught in an old Quonset hut from Vandenberg Air Force Base that Tony Dunn had bought to use as a science building. He had two of them, one for biology, and the other for physical sciences, and I figured that'd be where I'd spend my career.

It was dirty. Every day at exactly the same time, a garbage truck would come by the entrance to my labs, and the door was always open for ventilation, and all these clouds of dust would come in. It was always very dusty and dirty. Usually when we were having meals in the dining hall, a huge truck would roll by and then all this dust would come in. It was dust all the time.

One thing about the school's growth has been the effort to cover all that dirt with grass. You might take that grass for granted nowadays, but to put all those grassy fields in there, it takes an awful lot of work on the part of more than one fellow. I suppose Mike has five or six men working with him and they work on keeping the place beautiful all the time. That's what all the alumni remark about the first time when they come back. "Boy, has this place changed!

I got my nickname "Doc" from Ed Simmons, who was headmaster here for about ten years in the late 1970s and 1980s. It was because I have a doctorate degree in geology. I never had a nickname before in my life and he started calling me that in assembly, and the students picked up on it. I've been Doc ever since. It certainly is easier than pronouncing my last name.

The main reason I retired from teaching was - well, I was too old to continue teaching. For one thing, my hearing was beginning to go, and I now have hearing aids. But they still needed someone to drive the buses, so I drive the two buses now. And even there, we're getting bigger, because we have an assistant bus driver now. I hope we never have to have more than that! Driving the buses is a lot of fun. Beautiful countryside...

And one story that I've written about for the Dunn Journal is on the subject of team screaming. It involves girls. What happened was that Midland girls came down here for the first of two games for the Munger cup. And they beat our JV and tied our Varsity. And apparently they hadn't had a terribly good season, so that got them very excited. Well, when they have a game down there, they usually ask me to come up with a big bus and bring their teams down, 'cause they only have vans and they'd have to do a shuttle, and so I brought them down. They piled aboard all excited, and when they got to the driveway, they said, "Doc, please beep the horn."

I'd done that before - it's the same tradition we have here, beating the horn when you have a victory. So I got to the Midland driveway and started beeping the horn. It was cold outside. All the windows of the bus were shut. And these thirty-five girls swelled up their chests and let out the loudest noise I have ever heard.

When I was in the Navy, after my first four years of college, my position in a combat drill was right next to a pair of 40 millimeter anti-aircraft guns, automatic machine cannons. That noise is incredible if you have to stand next to it. The gunners all wear ear plugs. I figure that's where my hearing got damaged the first time.

Anyway, here I am driving along the Midland driveway, and they let out this unbelievable team scream. The windows are all closed, and so the sound is confined, and I can't take my hands off the steering wheel to turn off my hearing aids. They kept it up until we crossed the little bridge. The next day my ears were still ringing.

So this last game on Wednesday, I told the Dunn girls, "If you guys win, as we come back, you can see if you can scream louder than the Midland girls did." Well, they didn't win, but they tied, which meant that we keep the Munger cup. And so when we got behind the gym up here I started beeping the horn, and they made just as much noise as the Midland girls, but they kept it up longer. So they were really kind of the winners of the team-screaming contest.

The name of the trophy is the Munger cup, and it was given by our headmaster Jim Munger. For that game, his parents were there. Jim grew up on the Midland campus and the two schools are really tied quite closely together. His father and mother, who were headmaster and headmistress when I first came to teach here, were there for this game. When the game was about to start, the Midland girls lined up in a row, and all thirty of them gave Mrs. Munger a big hug and a kiss on her cheek. It's not something you see at an ordinary high school soccer game!

So that's the other side of my life. Driving the buses. It really is fun. In the old days, I had to sit at a game after driving the kids to the opposing school, and a lot of the time I didn't watch the game because I had a stack of lab notebooks this high that I was scoring. So there I'd be correcting these with all this yelling going on. Now I don't have to do that. I sit there and enjoy the game.

When I first started at Dunn, we had about twenty day girls and a few day boys, and about ninety boarding boys. We were just a little larger than Midland, not much. There's been quite an expansion with the dormitories built, and now we have boarding girls. I think that the quality of the students at Dunn improved as the school got bigger and started looking better.

One reason we wanted girls is because we were missing out on half of the good minds, and there were some boys who wouldn't come to a school without girls. And the boys mainly worked on their pecking order all the time. It was very aggravating. There was a certain amount of hazing. They'd wake someone in the middle of the night, spray shaving cream all over him, throw him into the swimming pool. If you reacted positively, you were okay. If you resisted or told, the seniors would make life miserable for you. A lot of that element.

When the girls came, the boys looked around and concentrated on making points with girls instead of being the big man in the pecking order. It always reminds me of fighting bulls. The steers calm the bulls down. So after we got some money to build girls' dorm, it became much more pleasant to teach here.

I do remember students in the earlier days as being a little tougher, maybe because the conditions were much rougher, so much dirt and dust. The fields were not as nice. And the food in the dining hall was very plain. Pam has worked miracles! One year we had a guy who fried everything and wasn't even very good at that. Mr. Simmons loved ice cream, so every night we had ice cream in the dining hall.

I come in the morning with some kids from Santa Maria. Then I have all day long. I live in Lompoc, and I used to go back and have lunch with my wife, but she got very busy selling houses, and it was kind of tiring to drive back and forth, so I started staying here, and one year I tutored a couple of kids who were being home-schooled by their parents. I tutored them in chemistry. We did the lab exercises right on the kitchen table. I stopped doing that when they moved on.

I enjoy walking. I go back and forth to Los Olivos by the back road, Park Avenue, or I do the circle. In high school I was a distance runner. I ran cross-country and track.. Eventually I started to get a pain in my hips. I stopped running, but I kept up walking. You have to walk pretty fast, not just a stroll. It beats running on a treadmill in your garage.

And in the last several years, I've been putting together a history of the school. It really involves gathering all the papers - the journals, the student newspapers, the photographs that are left over after the making of the yearbook.I've got several places marked off here about the middle school. For instance, in winter of 1979, there was an article - Ed Simmons invited anybody in the valley who had middle school age children who were interested to come to a meeting and they would talk about what parents expected in a school. So this little article is about the first step in the building of the middle school.

And here's a picture of house coming up a driveway. It became the third building in the middle school. The caption describes it as "Old Man Block's former home that stood at Mission Drive and Atterdag in Solvang since 1912."

At first it was a faculty home. Don Daves, the history teacher, lived in it his first year. Then we got some more faculty homes and the middle school was expanding and needed more room.I have a similar picture of the music building coming up the same driveway, missing its bell tower, 'cause that had to be taken off to get under the telephone wires.

This picture is Mr. Simmons addressing the student body of the first middle school, and here is the interior of the first building. I'm pretty sure this is the building we are in right now. I'm not sure you could recognize it now. This was twenty-two years ago.

Here - this is what Dunn Middle School looked like. There were two buildings -- the office, and the one we're in.

Look. There are the swings. And here they are having a Roman Festival. Bicycling trips were very popular, also.

And this happens to be a picture of my own wedding. My wife and I got married outdoors at an Arab horse ranch in Santa Ynez.

Anyway, that's what I do. I'm taking an awful lot of time with this, but I just wanted to show you what I'm doing as school historian so alumni can come back, thumb through this, and see what it was like. What was frustrating at the beginning was that the school yearbooks were collections of photographs, and some were very good, but if you wanted to know who was in the photo, it was very difficult to find out. There were no captions. So now there are boxes of photographs, and I take the yearbook, and the class list, and sometimes I consult with teachers and try to figure out who the people are. It's like piecing together a story.

For my own education, I went to public schools, and by some quirk of fortune, I grew up in a community that really wanted the best education they could get for their children, so we had schools that were always warm in the wintertime, with excellent teachers, good books. I lived in a place where I could walk to my grade school and the junior high and the high school, all kind of a circle not far from where I lived. It was near Chicago, and sometimes the snow was kind of deep, but it was fun. I didn't go away to school until I finished high school and then I went to college.

There were differences, of course. I think you would have laughed at the clothes we wore. We dressed up a little more. Not with coat and tie, but in lower grades we always wore shorts until we were forced by the cold to put on longer pants. When I first started school, it was the era when boys wore knickers, and then you had heavy socks that covered your calves. But that soon passed, and we got to blue jeans. In high school the boys wore lumberjack shirts and khaki trousers or blue jeans, and the girls - it was the era in which they wore sweaters, skirts, and bobby sox with loafers, The girls wore loafers, and you put a penny or a dime in your loafer. As for the teaching, you would probably think it was a little more like lecturing. But all teachers love to talk. They need brakes to slow themselves down.

The reason I am here now is probably because of a woman named Louise Mohr. She was my advisor when I was your age. Like most female teachers in those days, she was not married. There was nothing in the school regulations that said they could not marry, but it was something most of them never got around to. Anyway, back to Louise Mohr - I took a home economics course in the 7th grade. You made brownies and learned to sew. But my cousin and kind of sparked off each other and I didn't behave very well, so I had to be moved. Miss Mohr said, " I know just where you're gonna go. You're going into my public speaking class."

It gave me the chills to think about it. To stand up and give a talk in the seventh grade! For the last half of the year, I took this public speaking class, and it was a sweat every time I stood up to talk , but at the end of it, I had shown enough progress that she said, "Okay. There's no second year of public speaking, but I want you to be in my play."

I didn't enjoy this very much at the beginning, but once I got my lines memorized and we began to act, it was a lot of fun. And I always think that taking that public speaking class and being in that play - later in high school, I was in a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta - may have had a lot to do with my becoming a teacher later on.

I was in school during World War II. My older brother fought in the war. He got killed. I don't think anyone at home can really claim to have suffered during World War II unless they lost somebody. When my brother got killed, it was terrible. I don't think my parents ever really got over it. They lived for a long time after that, but they never got over it.

But until that time, the war at home basically meant that my dad had to do with less gasoline in his car. You had a ration card that was stuck to the window of your car and you presented that every time you went to get gas. Our diet was circumscribed a little bit. I happened to be a banana lover. I remember when my older brother graduated from junior high school, the family took him down to the drug store and bought him a banana split. Well, when my turn came, they took me down there, too, and woe is me, there were no bananas. The bananas all came from Central America, and German submarines had sunk all the banana boats, and so there were no bananas. We did without 'em. And we didn't eat quite as much meat, either.

It wasn't until 1949 - four years after the end of World War II - that the English gave up meat rationing and could eat as much as they wanted. The English really suffered. Great deprivations. But I don't think Americans really did. There were no bombing raids here. The Germans tried to land spies on our East coast but never succeeded. The spies were caught right away. And a Japanese submarine came up at California and scared everyone to death. In fact, a friend of mine had neighbors who moved from California back to the Midwest because they were so scared of the Japanese army landing on the Pacific coast. The Japanese had no plans to do that. Once they had bombed our fleet, they wanted the war to go away so they could enjoy their empire, but we didn't let them. So the Japanese subs scared Californians, put a leak into a couple of oil tanks, and that was it. I don't think we underwent any serious deprivation.

My brother was in Europe, in Patton's third army. It was terribly sad because he had survived the Battle of the Bulge and the campaign just before that, with Patton's army, and then I looked it up in the 87th Infantry Division record, and it showed that he was the last man in his battalion to get killed. Very soon after he got killed, the German army fell apart, and it was just a matter of getting into trucks and driving down the road in occupied Germany. He was the last man in his company even to be injured. He had survived an awful lot.

But discussion of war's impact would be incomplete without some mention of the way it changed the role of women. In the 1930's, our family included from two to five domestics, most of them young women for whom life on the family farm had become isolated and unappealing. They weren't paid much, but the got room and board while biding their time for better jobs and enjoying the social life of a town not far from Chicago. When war came, they quickly departed to jobs in factories or enlisted in the WACS or become nurses, and my mother found herself having to do much of the work of running a household. (Of course, I was old enough to help. My job was to fill the stoking machine in the basement with coal twice a day to keep the house warm.) At any rate, the war showed women they could do men's work, and they have never looked back.

Because of my older brother's tragedy, my father made me take ROTC when I went to Princeton. The Navy would pay me a small salary and you take one course a semester in Naval science or Naval engineering, you took a midshipmen cruise, then after you graduated, you were commissioned as an ensign in the US Navy and you were assigned for two years to a ship or shore station. Then you were free to continue in the Navy or leave the service in the reserve. I did my two years during the Korean war, a war that was fought mainly by the Army, and the Air Force to a lesser extent. But the soldiers are the guys that had to fight the Koreans and later the Chinese. And it was just as brutal as any war ever fought. But I think unlike Vietnam, we all believed it was the right thing to do. We were quite patriotic. World War II was only a few years back. The North Koreans had invaded South Korea and it looked like a giant beating up on some poor fellow. The government felt it was a ploy on the part of Stalin and his Communist regime to extend the Communist system all over the world. We felt we had to stop it.

Anyway, I was in Navy for two years. The Navy was not really involved in combat. The closest I got was when we were made the station ship for a town on the West coast of Korea. Soon after our ship came back from the Far East, I was sent back to the reserves, no longer part of the Navy. But the Navy was a very good place to be in that war, cause you got close to what was happening, but you didn't have to participate. We went through all kinds of exercises, but fortunately we never had to do any of it in actual combat. It was always exciting, riding in little boats to the beach, but not getting shot at.

I know that in growing up myself I was very shy and not a particularly good athlete, one of these bookish types. I always felt a little inferior because of that. You are bound to be hit by disappointment at one time or another. But the memories of the bad times begin to fade, and what sticks in your memory are the good times. Your problems look monstrous when you're growing up, but you look back and wonder why you were so upset. It's educational, or a mild ripple in your lifetime.

Talk to people about something that's worrying you. That's one of the greatest problems with boys. Girls do like to talk. They settle problems by talking. Boys tend to settle things physically or put things away without telling people - they sort of gunnysack things. Don't gunnysack. Talk to your friend first, or tell a teacher.

Come and visit. I'm in the library almost every day. Come and ask questions about school history. I'd be happy to see you.